New Orleans cinco años después

“He nacido en esta ciudad y nunca he querido vivir en otro lugar porque aquí hay todo lo que de verdad cuenta. Comida, música y gente fantástica”, dice Smokey Johnson, batería de Fats Domino en los años 50 y uno de los pilares de la producción de jazz, soul, R&B, funk y blues de Nueva Orleans. Si un huracán hubiera arrasado el 80 por ciento de otra ciudad, quizás muchas personas hubieran decidido reconstruirlo todo en otro lugar, más seguro. Pero en Nueva Orleans las palabras de Smokey Johnson las podría decir cualquiera, y con la misma mirada enamorada y fiel con la que las pronuncia levantando la cabeza para mirar desde su silla de ruedas.

Esta es la ciudad donde es mayor el número de personas que han nacido y muerto en el mismo lugar de todo el país.

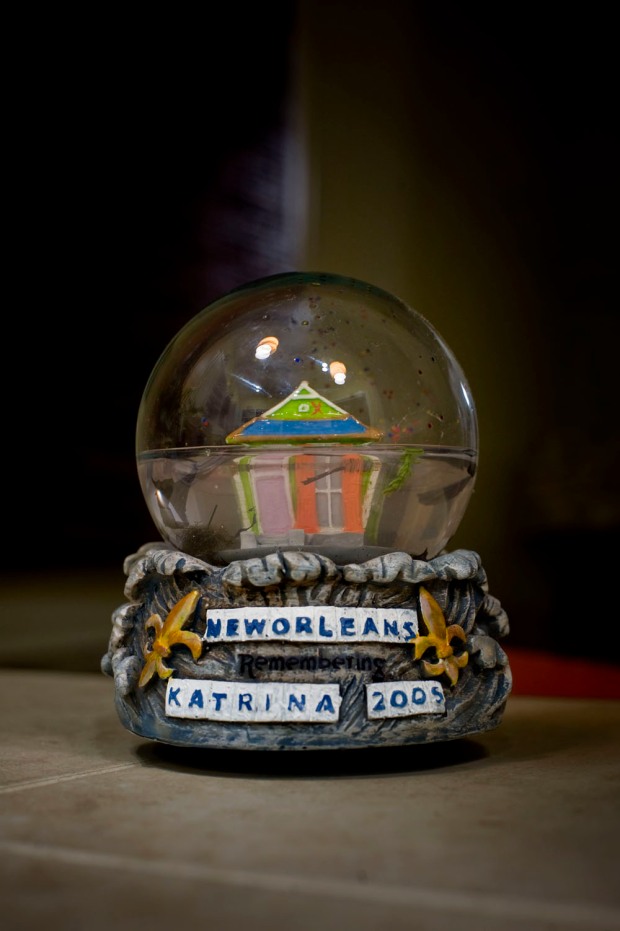

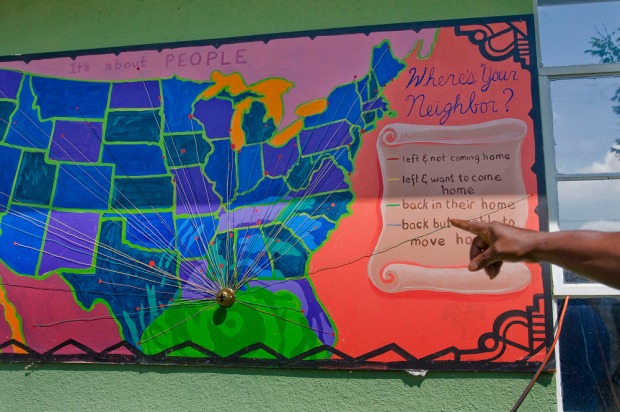

Desde hace cinco años “The big easy” (la gran despreocupada, como llaman en Estados Unidos a Nueva Orleans) tiene otro, triste, récord. Entre finales de agosto y los primeros de septiembre de 2005 aquí tuvo lugar la mayor catástrofe natural en la historia de Estados Unidos (hasta el pasado abril, cuando otra, de entidad aún por conocer pero posiblemente mayor, el derrame de petróleo de BP, golpeó la misma zona). Un quinto de la población (125 mil personas, mayoritariamente afroaméricanas) nunca ha vuelto.

Cuando, en la mañana del 28 de agosto de 2005, el entonces alcalde de Nueva Orleans, Ray Nagin, ordenó a toda la población ciudadana que evacuara, Omar Casimire, 62 años, pintor local, pensó que su deber de ciudadano era quedarse y ver lo que pasaría. Cogió una cámara de fotos, bolígrafos y una agenda y se trasladó a un hotel en una zona alta de la ciudad. En la mañana del 30 de agosto, cuando el agua desbordada por la ruptura de los diques de protección del Mississipi ya le llegaba al ombligo, Casimire salió hacia el Convention Center, donde había encontrado cobijo unas 15, 20 mil personas. Durante todo el día ayudó a rescatar de sus casas a cualquiera que se encontrara en los ocho kilómetros de recorrido que le separaban de su destinación final. Sólo el día después, tras haber pasado la noche en una iglesia junto con otras 30 personas, Casimire llegó, en el barco de una compañía petrolera, andando y en camioneta, al Convention Center.

“En el camino pasé delante del Superdome –casa del equipo de fútbol Saints, que en la primavera pasada ganó la liga estadounidense- y vi que había millares de personas fuera, tumbadas en el suelo. Así que cuando llegé al Convention Center y me encontré ante el mismo panorama, sin que hubiera ni policía ni nadie de prensa, enseguida me puse a recoger firmas y direcciones de todo el mundo, decidido a denunciar el gobierno”, recuerda. Sin agua ni comida y bajo 40 grados de temperatura, durante tres días y medio Casimire recogió unas 10 mil firmas y contactos, muchas hoy recogidas en formato entrevista en un libro en busca de editor. Las violaciones a mujeres y a niños y el olor a muerte de esos días le marcaron para siempre. Así que cuando, el 4 de septiembre, apareció la guardia nacional y las fuerzas aéreas y trasladaron a todo el mundo“dividendo arbitrariamente familias” hacia otros estados, Casimire llegó en elicóptero a Arkansas. “Nada más aterrizar supe que mi madre, que había llegado allí antes del huracán, había dejado de comer y se había muerto”, cuenta. “En lugar de denunciar el gobierno decidí entonces poner todas mis fuerzas en construir un monumento conmemorativo a todas las víctimas de Katrina”.

Cinco años después, el proyecto de la fundación “Katrina National Memorial Park”, creada en 2007 –la ciudad aún no tiene un monumento conmemorativo a las victimas del Katrina- pretende convertirse en un museo y centro de investigación (especializados en metereología e historia de los huracanes), observatorio y parque que ofrezcan formación y trabajo a los jóvenes de Nueva Orleans en las artes, la artesanía y la arquitectura del paisaje.

“Make your donation” pide su página web así como las de los numerosos proyectos nacidos durante estos años por toda la ciudad. Los 33 billones de euros de amortiguador económico del gobierno federal y los otros billones de compensaciones en seguros no han podido recuperar las 182 mil casas destruidas por el huracán –de las que 35 mil incluidas en el Registro Nacional de lugares históricos, el número más alto per capita de todo el país- ni reestablecer todas la infraestructura ciudadana. En barrios como el Ninth Ward, Gentilly o Lake View (de los más golpeados por el huracán), cinco años después aún faltan escuelas, supermercados, bibliotecas y medios de transporte.

La sociedad civil no se ha quedado a mirar. Como setas han aparecido y siguen apareciendo entidades no profit y voluntarios provenientes de todo los rincones del país.

En algunos casos una cosa ha llevado a la otra.

Cuando Oji Alexander, project manager neoyorkino de 36 años, supo que Barnes & Noble, la minorista de libros más grande del país, había creado una organización no profit de urbanización sostenibile para familias de bajos y medios ingresos en Nueva Orleans, le pareció una gran ocasión de echar un cable. En 2008 llegó como voluntario y algunos meses después, cuando debido a la creciente magnitud de trabajo “Project home again” (PHA) empezó a contratar personal y le propusieron quedarse, no se lo pensó dos veces. En dos años la entidad ha construido 45 casas y está acabando otras 25 para familias de dos a seis personas que perdieron las suyas a causa del huracán y cuyos ingresos anuales no sean inferiores ni superen la media de la zona (entre los 32 y los 70 mil dólares en el caso de núcleos de cuatro personas). Con tanto que tengan la capacidad económica de mantenerlas y pagar el seguro de hogar y el por inundaciones durante todo su estancia, las familias pueden intercambiar propiedas con PHA, sea cual sea su valor en el mercado, y recibir las nuevas casas a coste cero.

Todas las 100 viviendas en total que PHA pretende construir en el barrio de Gentilly, donde se fue a vivir la primera clase media afroamericana a finales de los años 50, están elevadas de casi dos metros del suelo (según ahora impone la ley en la zona), edificadas por arquitectos locales y realizadas con mecanismos (material reciclado de las casas demolidas, aislantes de espuma, deshumidificadores, pinturas bajas en V.O.C.) que hacen que sean un 60% más eficientes desde el punto de vista energético con respecto al estándar local. Sostenibilidad se ha convertido en una de las palabras más escuchadas en una ciudad que antes de Katrina no tenía ni un edificio “verde”. Y Brad Pitt en el nombre que más se le asocia. En sus tres años de existencia su fundación “Make it right”(MIR) ha construido unas 50 casas (prevé llegar a las 150), todas de diseño moderno y equipadas de paneles solares, en la parte baja del “Ninth Ward”, barrio pobre afroaméricano.

“Cuando Brad Pitt vino por primera vez a visitar la zona, yo era el único habitante de toda la calle”, explica Robert Green, 55 años, indicando el punto, ahora vacío, donde entonces se encontraba la rulot de FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) en la que vivió hasta hace poco. “Yo le di toda la información que tenía sobre los que habían sido mis vecinos y contacté con todos los que pude para explicarles el proyecto”. Para poderse apuntar las personas tenían necesariamente que vivir en el barrio antes del huracán. Según el “Green Building Council” norteamericano la comunidad de MIR se ha convertido en el mayor barrio verde de viviendas mono familiares de todo el país.

La vieja casa de Eva y Brenda Lewis, respectivamente de 72 y 64 años, algunas calles más allá, era poco más que una rulot de aluminio, hoy marchita y encogida como una lata para tirar. Como muchas en el barrio todavía llev una X pintada en la portal que atestigua el día –en muchos casos semanas después del huracán- en que la policía pasó a controlar si quedaban personas o animales por rescatar. Mientras enseñan la vivienda que ocupan desde el marzo pasado (que les llegó dotada de parquet, lavadora, secadora, microondas junto con un maquinario que controla sus gastos energéticos), las caras de ambas recuerdan a las de dos niñas que acaban de aterrizar en un parque de atracciones.

El gobierno federal les dio 120 mil euros por los daños subidos y con lo que les quedó de los 107 que gastaron para su nueva casa podrán pagar durante siete años el seguro de hogar, que incluye el panel solar instalado en el techo. Para ellas “el huracán ha sido lo mejor que podía pasar”.

La posibilidad de poder reconstruir, y mejor, no solo una ciudad sino una comunidad. Esto sin duda ha significado para mucha gente el Katrina.

Y también la posibilidad de visibilizar el malgobierno local, como demuestra la sentencia del juez federal que el pasado mes de noviembre estableció que gran parte de la inundación post-Katrina fue el resultado de la negligencia del Army Corps of Engineers, entidad federal, en la gestión y manutención del canal de navegación Mississipi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO). “La misma construcción del canal ha alterado el equilibrio ecológico de la zona y removido barreras naturales fundamentales contra las inundaciones como son los pantanos”, no se cansa de repetir Amanda Moore del National Wildlife Federation.

“Además, las compañías petroleras y las de gas han hecho su parte en dragar canales y construir ductos por los pantanos costeros de Lousiana, así que entre la construcción, el mantenimiento y la consiguiente intrusión de agua salada en los pantanos somos hoy una comunidad mucho más vulnerable a que se den eventos como el Katrina y más predispuestos a un impacto devastador ante otros como el recién derrame de petróleo”. El ritmo de extinción de los pantanos de la zona corresponde a un campo de fútbol cada 38 segundos. El juez, sin embargo, no ha concluido que la ruptura de los diques fuera causada por un defecto en la construcción sino únicamente en la manutención de los canales, por lo que la sentencia constituye un precedente sólo para los 80 mil habitantes de las dos zonas del Ninth Ward y San Bernardo –que ahora podrán pedir compensaciones- y no para los habitantes de la ciudad. Cinco años después sólo una parte de los diques de protección del Mississipi han sido reconstruidos. Lo que sí ahora la ciudad tiene es un plan de evacuación sistematizado diseñado para quienes no se puedan mover solos o no tengan como, dos de las condiciones que más se dieron durante el Katrina y que, entonces, no fueron tomadas en cuenta.

Como en La Peste de Albert Camus, ante una gran tragedia colectiva puede salir lo mejor pero también lo peor del ser humano. A menudo, ambas cosas. Y Katrina significó también la posibilidad de desahogar el odio, la violencia racial (estos dias el Departamento de Justicia esta llevando a cabo diversas investigaciones por violaciones de los derechos civiles y asesinato en los días post Katrina que ven involucrados a civiles y a policias) y la discriminación desde siempre presentes en la ciudad. Es del pasado mes de agosto la sentencia de otro juez federal contra Road Home, hasta ahora la mayor subvención federal para la reconstrucción, por discriminación hacia la propietarios afroaméricanos al calcular las ayudas utilizando los valores de las viviendas de antes del Katrina. Las viviendas de los barrios mayoritariamente “negros” tienden a venderse por menos que sus equivalentes por condiciones en zonas mayoritariamente “blancos”. No obstante, la sentencia no impone el recálculo de las subvenciones ya concedidas en cuatro anos a casi 128 mil propietarios.

Para otros, como Henry, taxista de 69 años, en cambio, el Katrina simplemente no representó una oportunidad. Además de perder a su hermana Henry, que vive con sus 10 hijos en el Ninth Ward, paga hoy casi el doble de alquiler –sin contrato- de lo que pagaba hace cinco años. Según alega su dueño la razón son los altos costes que tuvo que sostener para arreglar el edificio. Tras pagar la renta a Henry cada mes le quedan 400 euros.

La nueva casa de Robert Green está construida en el mismo terreno donde se levantaba la vieja, como recuerdan los tres escalones que ha querido dejar en memoria de lo que pasó. Para él, que en el Katrina perdió a su madre y a su nieta “esa fue una experiencia horrible, pero hicimos lo mejor que pudimos para convertirla en algo bueno”.

La vieja casa de las hermanas Lewis, algunas calles mas allá, aun lleva en el portal la X que la policía dejó semanas después del huracán, cuando fue a averiguar si quedaban personas o animales por rescatar. Toda la calle está llena. Según el Greater New Orleans data center, un grupo de investigación no-profit, más de 50.000 viviendas del núcleo urbano –alrededor del 27 por ciento- aun están vacías, la proporción mas alta que la de cualquier otra ciudad del país. La luchas, a menudo perdidas, de los propietarios con las compañías de seguro, la falta o pérdida de documentos que atestiguaran la propiedad –especialmente para las viviendas heredadas- y la oleada de contratistas fraudulentos que llegaron en la ciudad después de Katrina son todos elementos que influyeron significativamente en el fenómeno del “blighted houses” (casas vacías).

De las entre 1500 y 1800 personas que murieron y de las alrededor de 125 mil (un quinto de la población a principios de 2005) que no ha vuelto, muchas eran personas mayores que vivían en el Ninth Ward. Su falta convirtió en un barrio fantasma a la que desde siempre había sido la cuna de la música ciudadana. No podían que ser dos reconocidos músicos locales quienes crearan un proyecto que fuera a la vez de reconstrucción y encuentro de artistas y sonidos. El “Musicians’s Village”, concebido por Harry Connick Jr. y Branford Marsalis y parte de la organización cristiana no profit Habitat for Humanity, es un conjunto de 72 coloridas casas donde, a partir del 2006, empezaron a mudarse músicos de todos los barrios de Nueva Orleans. En su corazón se está levantando el centro de música dedicado al padre de Branford Marsalis, Ellis, jazzista como su hijo. Cuando acaben las obras el centro, que pretende servir tanto de escuela como de espacio para conciertos, estará abierto a toda la ciudadanía.

“Vine a vivir aquí por la fantasía de que la música que hagamos refleje una manera de vivir”, dice Fredy Omar, hondureño de 40 años, desde 18 en la ciudad y el primer músico en presentarse para el voluntariado de 350 horas en la construcción de las viviendas que constituye el requisito mínimo para acceder al “village”.

La idea que su arte sea una extensión de su comunidad está muy arraigada también en Rashida Ferdinand, 35 años, artista ceramista nacida en el Ninth Ward.

Gracias a dinero público tras el huracán Ferdinand pudo no sólo reconstruir sino ampliar su casa. Después fundó la organización Lower Ninth Ward Council for Arts and Sustainability, que además de proyectos de educación nutricional tanto en escuelas como en espacios públicos –en un barrio donde no se pueden encontrar productos frescos- trabaja para la rehabilitación de la escuela primaria del barrio quel lleva el nombre de la mayor de las estrellas ciudadana de todos los tiempos, Louis Armstrong.

El edificio, del 1930, aún lleva los anuncios de ese principio de curso de 2005 que nunca se llevó a cabo. Lo que no pudo el huracán y las inundaciones lo terminaron quienes durante estos años ha ido robando todo lo que se podía vender, en primer lugar acero y láminas de los tejados. Mientras pasea teniendo cuidado a donde pone los pies, Ferdinand va indicando qué vería en cada sitio. Allá un taller de cerámica, allá uno de estampa digital, al fondo un teatro para los grupos locales “que no tienen donde ensayar”, y después un espacio para exhibiciones también sobre la historia y la cultura del barrio y, porqué no, un café y una tienda de regalos. El patio de cemento, si encontrara financiación, Ferdinand lo sustituiría enseguida con un jardín botánico. En el barrio, donde viven unas 1800 personas, sólo hay una escuela pública abierta.

Como el 90 por ciento de las escuelas públicas de la ciudad el Louis Armstrong depende hoy del “Recovery School District” (RSD, distrito de recuperación escolar), que no tiene intención de reabrirla por no adecuarse desde un punto de vista estructural a lo estándares estatales de seguridad.

El RSD de Nueva Orleans nació en 2003 para intentar, desde el esfuerzo estatal (en Estados Unidos el sistema escolar es normalmente administrado a nivel local), recuperar aquellas escuelas consideradas “académicamente inaceptables” por el estado . En Nueva Orleans, donde a partir de la Ley de Derechos Civile anti segregación escolar de 1964 las familias “blancas” empezaron a sacar sus hijos de las escuelas públicas para que no se mezclaran con los “negros” hasta convertirlas en entornos poblados casi exclusivamente por afroamericanos pobres, las “aceptables” no llegaban al diez por ciento. Antes de Katrina sólo cinco escuelas pertenecientes al restante 90 por ciento habían abierto sus puertas bajo el nuevo sistema, que incluye escuelas “normales” y “charter” (subvencionadas y administradas también por entidades privadas o no profit, desde universidades hasta filántropos). Las segundas son sin duda la gran novedad que está revolucionando el sistema escolar de la zona.

“Katrina fue la oportunidad de acelerar el cambio que la escuela pública necesitaba y de responder mejor a las necesidades de los estudiantes”, dice Kristen Lozada, directora operativa del New Orleans College Prep., una de las 37 charters abiertas en la ciudad. “El 80 por ciento de nuestros estudiantes están por lo menos dos años atrasados desde el punto de vista académico. Ahora podemos juntar alumnos por su nivel y aceptar gente de todos los barrios de la ciudad y no, como solía ser, sólo del donde viven”, explica. “Es la primera vez que estos chavales sienten que tienen éxito”. Las cifras parecen confirmarlo. El 59 por ciento de los alumnos del sistema público están hoy en escuelas en línea con los estándares de calidad del estado (en 2004 eran el 28 por ciento). Los números positivos se constatan también en otros dos ámbitos claves de la ciudad. El turismo y la criminalidad. En el primer caso destaca la proliferación de restaurantes, que han pasado de 800 antes del Katrina a los 1100 actuales. Contemporaneamente el número de los crímenes ha pasado de un total de casi 29 mil en 2004 a casi 16 mil el año pasado. Si es verdad que hay menos gente que antes, lo mismo es verdadero para el cuerpo policial, que ha perdido 3000 oficiales. Lejanos son los tiempos del hurrication, cuando la llegada del huracán significaba descanso del trabajo, barbecues a la luz de las velas y el miedo era un sentimiento para pocos. Cada uno desde entonces ha perdido o ganado algo. Pero la voluntad de ser parte, activa, de la ciudad donde “cada día es fiesta” como la define Fredy Omar y “donde cualquiera puede ser lo quiere ser” como dice Ferdinand es tan fuerte y tan contagiosa que no hay Katrina que pueda con ella.

publicación en L’Unitá

ENGLISH VERSION

“I was born in this town and I have never wanted to live anywhere else because here there is everything that really matters. Great food, music and people”, says Smokey Johnson, Fats Domino’s drummer in the Fifties and one of the pillars of New Orleans’s jazz, soul, R&B, funk and blues output.

If a hurricane had devastated the 80 percent of another town, perhaps a lot of people would have decided to rebuild it all somewhere safer. But in New Orleans Smokey Johnson’s words could be said by pretty much anyone and with the same loving and loyal face with which he says them raising his head to look up from his wheelchair.

This is the city with the largest amount of people in the whole country who were born and have died in the same place.

“The big easy” has gained another, sad, record: Between the end of August and the beginning of September 2005 the worst natural disaster in the history of the United States happened here. Again, last April another disaster, The BP oil spill, whose consequences are yet to be known, hit the same area. One fifth of the city’s population, (125 thousand people, mostly African Americans) has never returned.

On the morning of the 28th of August, when Mayor Ray Nagin ordered a mandatory evacuation for all the citizens, Omar Casimire, 62 years old, a local painter, believed that his duty as a citizen was to stay and see what would have happened. He took a camera, pens and a notebook and moved to a hotel in a high area of town. On the morning of the 30th, when the water overflew from the town levels, Casimire headed to the Convention Center, where about 15-20 thousand people had found shelter. During the whole day he helped rescue from their houses anyone he met along his way, an eight kilometer trip separating him from his final destination. He spent the night in a church along with other 30 people. The next morning Casimire reached the Convention Center riding on an oil company’s boat, on a truck and on foot.

“On the way I passed the Super dome –home of the Saints, which last spring won the US league- and saw thousands of people lying outside. When I arrived at the Convention Center and I found a similar crowd, with no police or media covering the scene, I decided to take everyone’s signatures and addresses and then sue the government”, he recalls.

Without water and food and with 40 degree temperature for three days and a half Casimire collected around 10 thousand signatures and contacts, many of which are now listed in a book waiting to find an editor. The women and children who were raped and the smell of death he witnessed during those days scarred him for life. When on September 4th the National Guard and the Air Force showed up and, “dividing families” moved everyone to other states, Casimire arrived by helicopter in Arkansas.

“As soon as I got there I found out my mother, who had gotten there before the hurricane, had stopped eating and had died”, he recalls. “Instead of suing the government I decided then to put all of my strength into building a memorial for all Katrina’s victims”.

The Katrina National Memorial Park’s foundation was created in 2007, since New Orleans does not have a memorial for Katrina’s victims. It aims to become a museum and a research center focussing on weather and history of hurricanes; also it will include an observatory and a park offering learning and work to young people in the arts, crafts and landscape architecture.

“Make your donation” asks its web page like the many projects launched during these years in town. The 33 billions of Euros (almost 46 billion dollars) of Federal Government’s grants and the other billions in insurance couldn’t recuperate the 182 thousands of houses destroyed by the hurricane nor re-establish the whole city infrastructure. Neighborhoods such as the Ninth Ward, Gentilly or Lake View (among the most destroyed by Katrina) after five years still lack schools, grocery stores, libraries and public transportation.

The American population had no time to stop and take a look at the problem. However NGO’s and volunteers from all over the country started showing up in the area.

In some cases one thing led to the other.

When Oji Alexander, a 36 year old New York project manager, found out that Barnes & Noble had started a non profit organization of sustainable housing development for low and middle income families in New Orleans, he thought it was a great opportunity for him to help out.

In 2008 he arrived as a volunteer and some months later, due to the increasing amount of work “Project home again” (PHA) started hiring personnel, he was offered a job which he accepted promptly. In two years the organization has built 45 houses and it’s finishing another 25 for two to six member families who have lost theirs because of the hurricane. Such families are all middle class with a 32 to 70 thousand dollars annual income per family. All they have to do is sustain themselves and pay for home and flood insurance. Families can swap property with PHA, whatever the market value of their houses, and receive the new houses for free. All the 100 houses PHA wants to build in the Gentilly neighborhood, where the first African American middle class started to move in the fifties, are almost two meters high from the ground (according to what the law now establishes for the area), built by local architects and realized through mechanisms (from recycled material from the demolished houses to foam insulating or low V.O.C. painting) which make them 60% more energy efficient than the local standard. The Gentilly neighborhood is where the first African American middle class started to move in during the fifties. Here PHA will build one hundred houses with the highest standards in energy savings and recycling. They will be built with basements elevated up to two meters from the ground according to the new local regulations.

Sustainability has become one of the most heard words in a town that, before Katrina did not even have one “green building”. And Brad Pitt is the name most associated to it.

In its three years of existence his foundation “Make it right” (MIR) has built around 50 houses (plans on getting to 150), all equipped with solar panels in the Lower Ninth Ward.

“When Brad Pitt came to the neighborhood with the intention of doing something there was nobody but me living in a FEMA’s trailer”, explains Robert Green, 55 years old. “I gave him all the information I had about my old neighbors and got in touch with all I could to explain ‘em the Project”. Only people living in the area when Katrina hit can apply for it. According to the US “Green Building Council” the MIR community was converted in the country’s largest “green neighbourhood”

Eve (72) and Brenda (64) Lewis’s house, some streets away, used to be little more than an aluminium trailer, and is now a shrivelled and smashed shell. Like many houses in the neighbourhood, it still sports the indicatory X sign on the front door, indicating FEMA’s ubiquitous house spot check sign inscribed days – and in many cases weeks after the hurricane hit- indicating the number of people or animals in need of rescue. In showing us their house they have been living in since last March, their faces had the excited gleam of two little kids at a funfair. The Federal Government awarded them 120 thousand Euros (166 thousand dollars) for damages suffered and with what remains of the 107 thousand (148 thousand dollars) they spent on the new house they will be able to re-pay seven years worth of their home insurance premium, as well as the new solar panels on their roof. In their words “the hurricane has been the best thing that could have happened”.

The chance to rebuild, not only a town but a whole community is undoubtedly what the aftermath of Katrina has meant to many people.

Katrina was also a chance for the bad governance at local, state and federal level to be highlighted, as demonstrated by the sentence carried out by the federal court which found that some of the worst flooding cases following hurricane Katrina were caused by poor maintenance by the Army Corps of Engineers of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO), a major navigation channel. “Both the construction and maintenance of the channels, canals and pipelines dredged by oil and gas companies -with the saltwater intrusion that follows- have led to a deterioration of the coastal ecosystem around New Orleans and have removed natural vital storm surge protections such as the wetlands”, Amanda Moore of the National Wildlife Federation doesn’t get tired of repeating this. “The loss of wetlands along Louisiana’s coast made communities more vulnerable to both Hurricane Katrina and the oil spill. In the case of Katrina, the state of the coast made communities more vulnerable to storm surge. In the case of the oil spill, the state of the coast made the impact on wetlands even more of a devastating blow than it would have already been if we had a healthy coast”. The local wetlands are vanishing at an alarming rate – a football field every 38 minutes. The federal judge’s decision, though, considered it was the maintenance rather than the construction of the canal itself, which led to widespread flooding, therefore the liability applies only to damage around the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans and St. Bernard Parish, east of the city and only sets up a precedent for the 80,000 people living in these areas and not for all the New Orleans.

Almost five years after Katrina only one part of the town’s levees have been rebuilt. However the city does now have a systematized evacuation plan designed for those who cannot move by themselves or do not have the means to, two conditions which were not taken into account then.

Like in Camus’ “The Plague” a collective tragedy can bring out the best but also the worst of humanity. Often, both at the same time. Katrina gave vent to some of the deep seeded and in some cases deep running hatred, racial violence (at present the Department of Justice is carrying out investigations for violations of civil rights and murder in the days after Katrina involving police officers and civilians alike) and discrimination ever-present in this most diverse of American cities. Last August another federal court ruled that the Louisiana Road Home programs’ method of calculating grants discriminated against African American homeowners because it used pre-storm home values. Homes in largely ‘black’ neighborhoods tended to see less than equivalent homes in largely white areas. The sentence, however failed to impose a recalculation on the rebuilding grants given over four years to almost 128 thousand home owners.

However, for the vast majority Katrina was an unqualified catastrophe. Residents such as Henry, 69, a taxi driver from the town’s Ninth Ward, who not only lost his sister in the hurricane but now lives with his 10 children paying almost double in rent –with no contract- than before the hurricane. According to his landlord the reason for this is the high expenses he had to bear to fix the building. After paying the rent every month Henry only has 400 Euros (553 dollars) left.

Robert Green’s new home has been built on the same ground as his old one, as the three stairs he left as a memorial of what happened show. To Mr. Green, who lost his mother and grand-daughter in Katrina, “it was a very bad situation but we did all we could to turn it into a good thing and move on”.

The Lewis sisters’ house, some streets away, carrying the FEMA X left on its doorway a few weeks after the storm the X police left during their house check weeks after Katrina. The street is full of the signs and according to the Greater New Orleans data center, a non-profit research group, more that 50 thousand houses of the town –around 27 percent of the total- are still “blighted”, the highest percentage of any other city in the country. The disputes –often lost- with insurance companies, the lack or loss of ownership documents– especially where inherited houses are concerned- and the spate of bogus contractors that arrived after Katrina are all elements influencing significantly the so called “blighted houses” phenomenon.

Of the 1500 to 1800 thousand people who died and of the 125 thousand (a fifth of the population at the beginning of 2005) who have not returned, many were elderly, living in the Ninth Ward, thus turning this place once cradle to the Big Easy’s music culture, into a veritable ghost neighborhood. None but two of the city’s best loved local musicians could set up a project for the reconstruction of the city’s music heritage and a meeting point for artists and sounds.

The “Musicians’ Village”, conceived by Harry Connick Jr. and Branford Marsalis -a cornerstone of the New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity (NOAHH) post-Katrina rebuilding effort- is a community of 72 colorful houses where, since 2006, musicians from all the city’s areas started to move. In its heart is now being erected the Ellis Marsalis center for music, named in honor of Branford’s father, the New Orleans native and legendary jazz pianist and teacher. When the center will be complete, it aims at becoming both a school and a space for concerts, will be open to the whole citizenry.

“I came here for the fantasy that the music we make could reflect a way of living”, says Fredy Omar, 40 year old from Honduras, for 18 in town and the first musician in standing up for the 350 hours volunteering in the building construction which constitutes the minimum requirement to access the “village”.

The idea that one’s art is the extension of one’s community is deeply rooted also in Rashida Ferdinand, a 35 year old visual artist, born in the Ninth Ward. Thanks to public grants Rashida could not only rebuild but also enlarge her house after the hurricane. She then founded the Lower Ninth Ward Council for Arts and Sustainability organization which organises education programmes in schools and in public spaces –in a neighborhood where it’s impossible to buy fresh products- also works to restore the primary school named after the brightest start ever of the city music, Louis Armstrong. The 1930’s building still carries announcements dating back to the beginning of 2005. As she makes her way carefully across the ruined centre, Ferdinand points out what she dreams of seeing in every corner of the building. A ceramic workshop, a rehearsal room for the local groups “who don’t have where to do it”, a contemporary art gallery and exhibit spaces dedicated to the history and culture of the Lower 9th Ward further and, why not, a gift shop and a café. If she found the grants, Ferdinand would immediately turn the gardens into botanical gardens, farming area and community gardens. In the neighborhood, where around 1800 people live, there is only one public school open.

Like the 90 percent of the city’s public schools, Louis Armstrong is now part of the “Recovery School District” (RSD). The Nueva Orleans RSD was created in 2003 to try to recover those schools considered “academically unacceptable” by the state. By then not 10 percent of New Orleans schools were deemed as “acceptable”. Before Katrina only five schools belonging to the other 90 percent had opened under the new system, which includes “normal” and “charter” schools (funded and run also by private or non profit entities, from universities to philanthropists). The charters are undoubtedly the big news that’s stirring up the local school system.

“Katrina was the chance to accelerate the change public school needed and to better meet students needs”, says Kristen Lozada, Director of Operations at the New Orleans College Prep, one of the 37 charters open in town. “80 percent of our kids are two or more years behind academically. With the new system we can put them together depending on their level and also accept students coming from any area of town and not, like it used to be, only those living in this neighbourhood”, she explains. “For many of these kids it is the first time ever they actually see success”. Statistics seem to confirm it skating that 59 percent of the public school students are now in schools that meet the state standards (in 2004 it was only the 28 percent). Positive numbers are ascertained also in other key spheres of the town. Tourism and crime. Concerning tourism, the proliferation of restaurants stands out, which went from 800 before Katrina to the current 1100. On the other side the number of crimes has decreased from around 29 thousand total in 2004 to almost 16 thousand last year. If it is true that there are less people living in town, the same is true for the police forces, which have lost 3000 officials.

Far-off are the days of the hurricanes, when the arrival of the hurricane meant a break, barbecues by candle-light and fear was not a common feeling. Since then everyone has lost or gained something. But the will of being an active part of the city where “every day is a party” like Fredy Omar says and where “anyone can be whatever he or she wants to be”, like Ferdinand says has not changed and it is so strong and contagious that not even Katrina seems to be able to destroy it.

Geniales como siempre, tus reportajes. Qué fantástico tu blog. Gracias por compartir experiencias e imágenes. Un abrazo grande.

Pingback: New Orleans cinque anni dopo il Katrina | elenaledda

Registramos para su website articulos en mas de de top, publicando un articulo distinto cada vez que publicamos para no ser considerado contenido duplicado Directorios de Articulos a un precio muy rentables%7